Why do we behave the way we do?

Can the answer to this question help us change our less desirable behaviors?

Changing less desirable behaviors can help individuals, communities, and our environment.

However, behaviors can be highly ingrained and become habits we perform automatically without thinking. This poses a significant challenge to changing these behaviors.

To design effective interventions with which to change behavior, it is useful to understand the theories and models of behavior change.

This article will cover the leading theories and models, as well as an interesting study and some simple techniques to help your clients change their behavior.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

Behavioral change is about altering habits and behaviors for the long term. The majority of research around health-related behaviors (Davis, Campbell, Hildon, Hobbs, & Michie, 2015) indicates that small changes can lead to enormous improvements in people’s health and life expectancy. These changes can have knock-on effects on the health of others (Swann et al., 2010).

Other behaviors that are the target of change interventions are those affecting the environment, for example:

Some behavior changes may be related to improving wellbeing, such as

These are just a few examples of behavior changes that many have tried at some time in their lives. Some changes may be easy, but others prove quite challenging.

There are many theories about behavior and behavior change.

In a literature review by Davis et al. (2015), researchers identified 82 theories of behavior change applicable to individuals. We will discuss the most frequently occurring theories and models in this article.

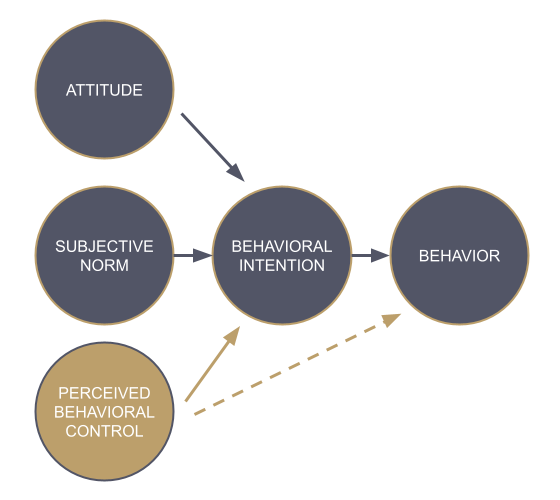

Fishbein and Ajzen developed the theory of reasoned action in the 1970s. This theory posits that behaviors occur because of intention, and intention is influenced by personal attitude and the perceived social norm (Madden, Ellen, & Ajzen, 1992).

This means that the more positive a person’s attitude toward changing their behavior and the more others are doing the desired behavior or supporting the behavior change, the stronger the person’s intention to change their behavior will be and the more likely they are to successfully change it.

In the 1980s, Ajzen extended this model to incorporate perceived behavioral control as an influencer of intention and sometimes as a direct influence on behavior (Madden et al., 1992).

Perceived behavioral control is a person’s confidence in their capability to perform the behavior and whether they believe they can overcome barriers and challenges. This extended model is known as the theory of planned behavior and accounts for more variation in behavior change than the theory of reasoned action (Madden et al., 1992).

The theories of planned behavior/reasoned action

The image above, adapted from Madden et al. (1992), shows the theory of reasoned action in gray and the addition of perceived behavioral control in brown to create the theory of planned behavior.

Here is a useful YouTube explanation of the theory of planned behavior.

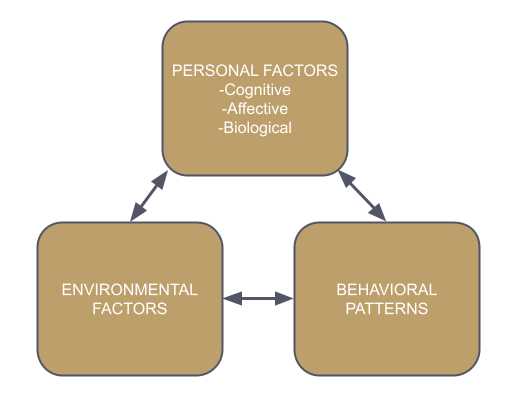

The social cognitive theory, proposed by Bandura in 1986, is an expansion of his earlier social learning theory, in which he states that many behaviors are learned by observing others in our social environment (Bandura, 1999).

For us to adopt a behavior, we have to pay attention to the behavior being modeled, remember it, and reproduce it. We may be rewarded for this, which reinforces the behavior, or punished, which reduces the likelihood we will do it again. However, Bandura acknowledged that there is more to adopting a behavior than this.

He expanded his theory to include personal factors of the individual: cognitive, affective, and biological. This includes an individual’s personal resources and abilities, their perceived self-efficacy (capability of performing the behavior), their expectations of the costs and benefits of changing their behavior, and the perceived barriers and opportunities that may help or hinder them.

Bandura emphasizes that we are the agents of our own development and change, and our perceived self-efficacy and outcome expectations play an important role in determining our actions. Our social surroundings can aid or inhibit our goals by providing opportunities or imposing restrictions, which in turn can affect our perceived self-efficacy and outcome expectations for next time (Bandura, 1999).

A model of this theory is shown below, highlighting a bidirectional relationship between an individual’s personal factors, the environment, and their behavior, with each factor influencing the others.

Social cognitive theory model

YouTube has this good summary video on Bandura’s social cognitive theory.

Theories can be used to build models and frameworks that have more practical applications and can be used to develop interventions. Three frequently occurring models are explained below.

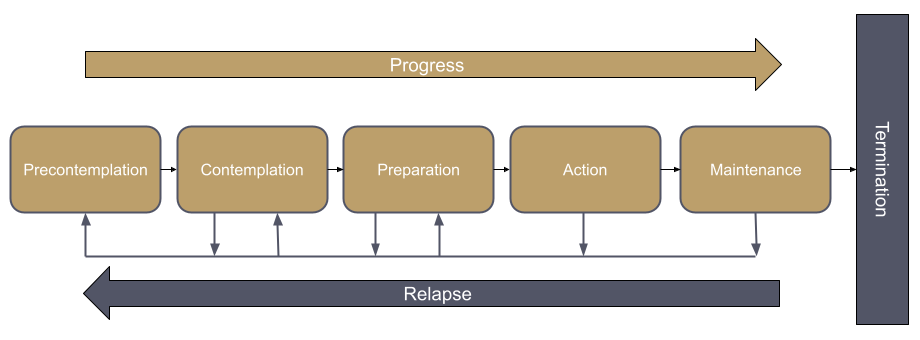

Otherwise known as the stages of change, this is the most frequently occurring model in the literature. The transtheoretical model was developed by Prochaska and DiClemente in the late ’70s and suggests six stages of behavior change (Prochaska, 1979; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982).

Identifying the stage an individual is in helps health professionals, coaches, and therapists provide targeted interventions for that stage.

The six stages of change are:

The transtheoretical model/stages of change

Here is a short YouTube animation about the transtheoretical model of change.

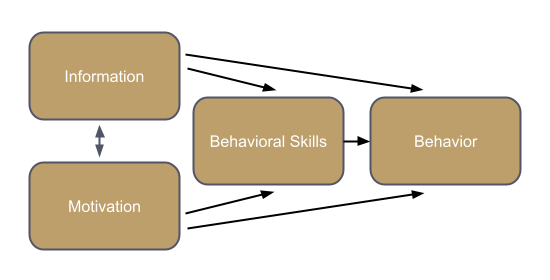

This model was designed by Fisher and Fisher (1992) after reviewing the literature on changing AIDS-risk behavior. They propose three key factors that influence behavior change:

Information includes automatic thoughts about a behavior as well as consciously learned information. Motivation includes both personal motivation, the desire to change behavior for oneself, and social motivation, the desire to change behavior to fit into the social environment.

Information and motivation influence behavioral skills, which include objective skills and perceived self-efficacy. The combination of information, motivation, and behavioral skills influences behavior change (see image below).

As a helping professional, increasing the amount of information your client has, helping them find their motivation, or increasing their objective behavioral skills or perceived self-efficacy could help them change their behavior.

The information–motivation–behavioral skills model (Fisher & Fisher, 1992)

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises, activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!”

— Emiliya Zhivotovskaya, Flourishing Center CEO

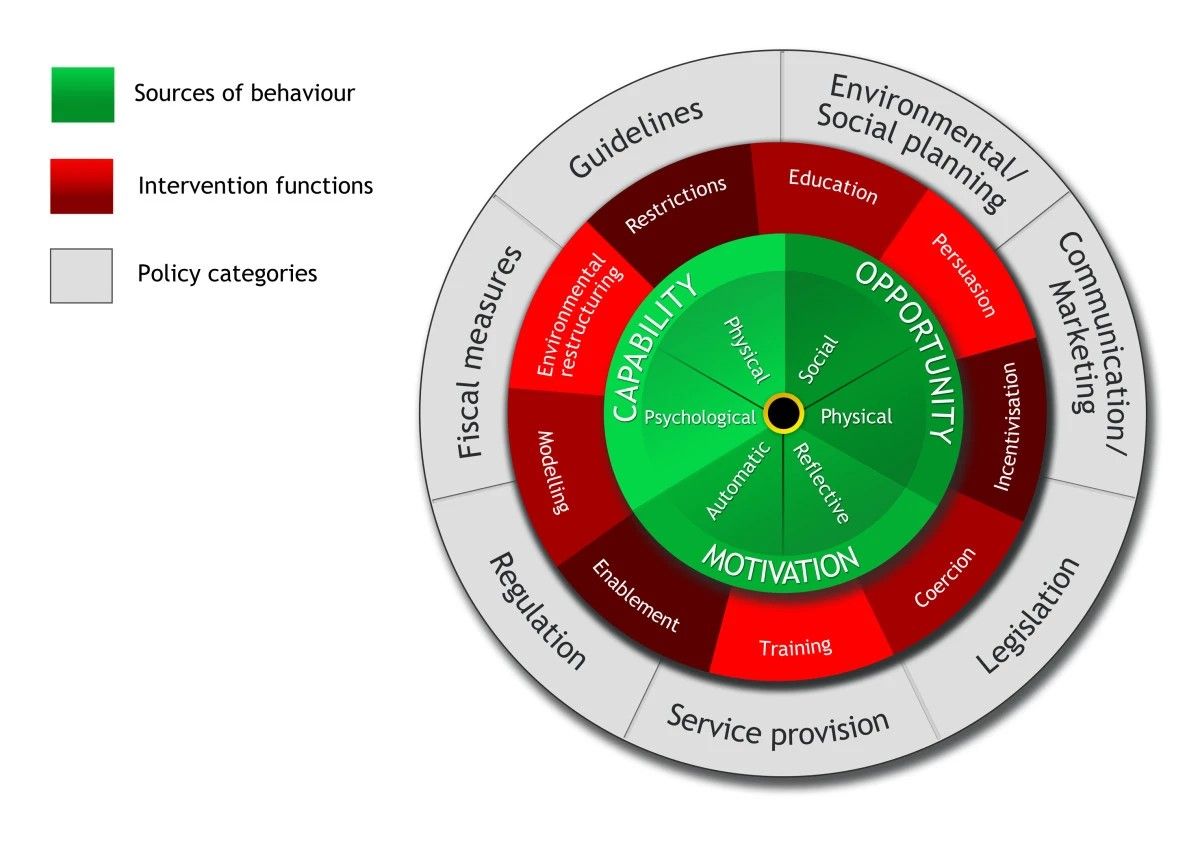

In 2011, Michie, van Stralen, and West pulled together different behavior change frameworks to create a behavior change wheel. The aim of this was to provide guidance for policy makers and those performing behavioral interventions, based on the existing evidence.

The behavior change wheel from Michie et al. (2011)

The hub of this wheel, the most relevant part for us, involves three conditions: capability, opportunity, and motivation.

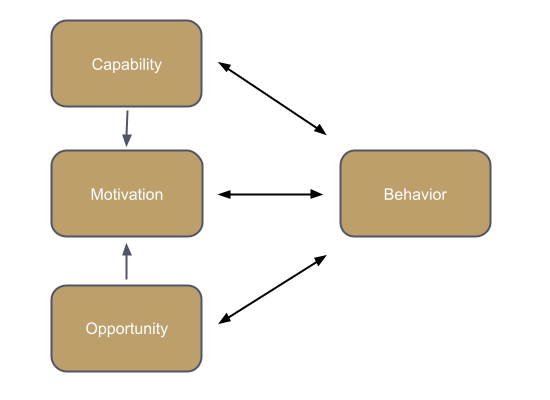

These components have been put together to form the COM-B model, where opportunity and capability influence motivation, and all three factors influence behavior. Improving any of these areas could help your client change their behavior.

COM-B model (Michie et al., 2011)

In a fascinating study, Verplanken and Roy (2016) tested the habit discontinuity hypothesis, which suggests behavioral changes are more likely to be effective when undertaken in a period when there are already significant life changes occurring.

They wanted to see if interventions to promote sustainable behaviors were more likely to induce behavior change in people who had recently moved.

They studied 800 participants, half of whom had moved within the previous six months. The other half lived in the same areas and were matched for home ownership, house size, access to public transport, and recycling facilities, but had not recently moved.

The researchers gave an intervention on sustainable behaviors to half of the movers and half of the non-movers, and compared self-report data on behaviors before and after the intervention.

After accounting for environmental values, past behavior, habit strength, intentions, perceived control, personal norms, and involvement, they found that the intervention had the strongest effect on the self-reported sustainable behaviors of those who had recently moved within the last three months, termed the “window of opportunity.”

This supports the habit discontinuity hypothesis: behavioral changes are more likely when individuals are already undergoing significant life changes.

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.